CMU's Response to Antisemitism Lawsuit

A Carnegie Mellon University graduate student of architecture filed a lawsuit alleging antisemitism, and the university’s response could be improved. The federal complaint describes incidents since 2018, including a professor’s actions and comments to the student and the student’s reports to the DEI office and the Title IX office, which she says discouraged her from filing a formal complaint.

The university’s response sounds like ChatGPT wrote it. The president uses well-worn phrases for these types of statements, as if they were pulled from those who had faced similar situations, regardless of whether the response was well received or ethical. The most glaring sentence is, “We take these allegations very seriously, are reviewing them closely and plan to respond appropriately.” Of course they do and they will. This is no great statement of accountability: the university has little choice after receiving a federal complaint.

“Values” appears three times in the short statement, the last one linking to the university’s “shared values” that no one but me will read. If they did, they would see that all eight values could appear on any university’s website—or that of most for-profit, non-profit, or governmental organizations.

I am sympathetic. University presidents are leading in extremely challenging times, when no answer, no action will satisfy everyone. This has always been true for organizational leaders, but now seems particularly rough. Related: I found Sophia Rosenfeld’s article, “I Teach a Class on Free Speech. My Students Can Show Us the Way Forward,” to be a poignant, hopeful summary of the current situation.

BP Focuses on Misleading Statements, Not Relationships

BP is unusually blunt in publicizing the results of an investigation against the former CEO. But the focus is on misleading, not inappropriate relationships.

I analyzed a previous statement about this situation in which the Board used softer, ambivalent language:

Mr Looney has today informed the Company that he now accepts that he was not fully transparent in his previous disclosures. He did not provide details of all relationships and accepts he was obligated to make more complete disclosure.

This recent statement holds little back:

Following careful consideration, the board* has concluded that, in providing inaccurate and incomplete assurances in July 2022, Mr Looney knowingly misled the board. The board has determined that this amounts to serious misconduct, and as such Mr Looney has been dismissed without notice effective on 13 December 2023. This decision had the effect of bringing Mr Looney’s 12 month notice period to an immediate end. [The asterisk refers to a note about the interim CEO.]

In detail, the board describes compensation decisions, which amount to the CEO forfeiting about $41 million. Some compensation from 2022 also will be clawed back.

I am curious about the board’s reasoning. “This amounts to serious misconduct” refers to his misleading the board, not the relationships. Are these not also considered misconduct? Or are they just harder to prove—or to talk about?

I also note that the board avoids saying Looney “lied,” which means making a false statement. Wasn’t that the case? “Providing inaccurate and incomplete assurances” sounds like lying to me—maybe not the “incomplete” ones but the “inaccurate” statements. “Mislead” sounds more professional, subtler, which makes the news release blunt, but not that blunt.

Missing Communications Prep in University Testimony

If students need an example of the value of crisis communication, the university presidents’ testimony this past week proves the point. An embarrassment to all three colleges, Harvard, University of Pennsylvania, and MIT, the public hearing ended with apologies from two of the leaders and the resignation of Penn’s.

A New York Times article describes how a law firm prepared both the Harvard and Penn presidents. As business communication faculty know, legal advice protects the organization from litigation. But crisis communication advice protects the organization’s, and the leader’s, reputation.

To a PR expert, the lack of proper preparation, including practicing answering a range of difficult questions, is clear. NY Representative Elise Stefanik asked the most pointed question: “Does calling for the genocide of Jews violate Harvard’s rules of bullying and harassment? Yes or No?“ Presidents focused on speech vs. conduct and said it “depended on the context.” Harvard President Claudine Gay gave vague answers about Harvard’s “commitment to free expression” and “rights to privacy.” Stefanik and other lawmakers accused Gay of not speaking with “moral clarity.”

To me, the character dimension most at issue is integrity—the universities’ commitment to DEI and free speech, yet what some see as an inconsistent application. All three presidents issued statements after the hearings:

Harvard: President Gay issued a short statement, contradicting her response to Stefanik’s question: "There are some who have confused a right to free expression with the idea that Harvard will condone calls for violence against Jewish students. Let me be clear: Calls for violence or genocide against the Jewish community, or any religious or ethnic group are vile, they have no place at Harvard, and those who threaten our Jewish students will be held to account.” In an interview with the Harvard Crimson, she apologized and demonstrated compassion, “I am sorry,” “Words matter,” and “When words amplify distress and pain, I don’t know how you could feel anything but regret.”

MIT: In a statement, President Kornbluth linked to her opening statement and wrote generally about community and fighting against hate. She didn’t directly address the hearings or her responses to questions.

Penn: Demonstrating humility in a video message, President Magill admitted that she should have responded differently: “In that moment, I was focused on our University’s longstanding policies aligned with the U.S. Constitution, which say that speech alone is not punishable. I was not focused on, but I should have been, the irrefutable fact that a call for genocide of Jewish people is a call for some of the most terrible violence human beings can perpetrate. It's evil—plain and simple.”

Magill has since resigned from Penn along with the Board chair. Alumni pressure at Penn was particularly strong even before the hearings. Hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, possibly the loudest voice, is calling for the other presidents to resign as well. A Harvard graduate, Ackman wrote an additional letter to his alma mater, a good example of persuasive communication if you’re prepared to manage fallout from a heated class discussion.

WSJ’s Analysis of Spotify’s Layoff Email

The Wall Street Journal analyzed Spotify’s layoff email announcing a 17% workforce cut—about 1,500 people. For the most part, comments align with what business communication faculty teach about writing bad-news messages.

Here are a few notes about the WSJ comments. Students could use these components to compare the four company messages the WSJ mentions—Amazon, Meta, and Salesforce in addition to Spotify’s.

Subject line: The WSJ is right that most of these emails have a subject line that sounds “innocuous”; all four have “update” in the title. (The Journal writer calls it a “title” because that’s what we see online, but to employees, it’s an email subject.) What’s more relevant about the use of “update” is the organizations’ reminder that bad news is coming. Layoffs should not be a surprise, and company leaders want all stakeholders to know that they have properly prepared employees.

When the news is broken: Older communication principles taught the indirect organization style for bad-news messages (with context/reasons first), but we have little evidence to support this structure, which tends only to make the writer feel better (for example, see Microsoft Layoff Email). In these four email examples, the news (including a workforce percentage) is clearest in the second paragraph. An interesting study would assess how quickly employees read the first paragraph, scanning for the bottom line.

Yet, the second paragraph is probably “upfront” enough given that the layoffs should be expected. But the news tends to come at the end of that second paragraph, an indirect paragraph structure in itself. In 2020, Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky broke rank and wrote in the first paragraph (albeit at the end): “today I have to share some very sad news.”

How context is explained: What’s interesting to me is whether the leader takes responsibility for the need to layoff, say, 17% of the workforce. I’m impressed by Marc Benioff’s accountability and humility (learning from mistakes) at Salesforce: “we hired too many people leading into this economic downturn we’re now facing, and I take responsibility for that.” Andy Jassy at Amazon admits, “we’ve hired rapidly over the last several years.” Mark Zuckerberg focuses on “efficiencies," leaving us to wonder where the inefficiencies came from. The Journal writer notes, “executive mea-culpa has become another staple of the layoff letter,” but I don’t see many as explicit as Benioff. Others point to changing conditions that were difficult to predict. Although that may be true, exuberant hiring was still a mistake, by definition, given the negative results. A leader could own it.

Balancing those leaving and staying: The Journal writer points out a difficult part of writing layoff memos—the tone for each group: “Executives want to acknowledge the contributions of the laid-off employees, while quickly then pivoting to explain why the company will be fine without them.” This is why one massive email to multiple audiences is an imperfect approach. But it’s probably best for consistent, timely, and transparent communication.

How people are affected: Let’s face it: what employees reading these emails care most about is, what about me? Spotify is clear about what to expect next: “If you are an impacted employee, you will receive a calendar invite within the next two hours from HR for a one-on-one conversation.” A tech, rather than a personal, contact isn’t great, but, again, it’s best for quick, consistent communication.

Compensation and benefits for people leaving: I used to think this was inappropriate to include in layoff emails sent to people not affected, but I’ve warmed up to the idea. Now that these emails are made public, the company needs to assure all stakeholders that they are being fair, if not generous. Spotify received accolades for its process from people like Dave Lehmkuhl, whose LinkedIn post got more than 57,000 likes so far.

Jargon: The Journal writer jokes, “Ding, ding, ding: If you had ‘right-sized’ on your corporate-layoff-memo bingo card, you’re a winner.” Students will find other jargon in these emails, but not an abundance of it. CEOs and their writers want to avoid the likely ridicule.

Rallying those remaining: Does that last email section describe a place where those left behind want to work? Ending on a positive note is critical, particularly if the message is public for shareholders and consumers to read. But only the primary audience, employees, can answer the question—and perhaps only in a year from now will they know for sure.

Goldman's PR Problem

On the podcast The Prof G Pod, Scott Galloway discusses how the media portrayed the end of an Apple-Goldman consumer finance partnership. He blames Goldman communication staff for the poor reflection on the company.

From about 19:15 to 25:00 on the segment, “Goldman and Apple Part Ways” [NSFW], Galloway and cohost Ed Elson describe how the story was framed in inflammatory headlines, for example, WSJ’s “Apple Pulls Plug on Goldman Credit-Card Partnership” and Business Insider’s “Apple Wants to Cut Ties with Goldman Sachs.” They say the headlines are surprising because Goldman initiated the split, not Apple.

Galloway provides two reasons for the slant. First, he blames Goldman for not managing the message. He said, “Quite frankly, the comms people at Goldman didn’t do their job.” He also said, “The core competence now of every CEO has to be storytelling.” Second, he said the media tends to favor Apple.

They also discussed what gets read. Ed Elson asked for ChatGPT’s help in writing headlines to get clicks, and the results were similar to those published.

Despite Galloway’s usual cursing, the segment is useful for students to learn about corporate communication, particularly the importance to company valuation.

Words of the Year

Every year, Oxford University Press and Merriam-Webster identify a “word of the year,” arrived at in different ways. This year’s winners are “rizz” (slang for charisma) and “authenticity,” respectively.

Oxford University Press describes the word of the year:

The Oxford Word of the Year is a word or expression reflecting the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of the past twelve months, one that has potential as a term of lasting cultural significance.

Oxford University Press’s process is more extensive than Merriam-Webster’s. The Word of the Year website, which updated a couple of days after the word was announced, asked the public to “Help us choose the four finalists, before the final word for Oxford Word of the Year 2023 is revealed by our language experts.” About 30,000 people voted on word pairings, for example, “Swiftie” vs. “de-influencing,” and “rizz” vs. “beige flag.”

On an FAQ page, the organization answers the question, “How is the word chosen?”:

The candidates for the Word of the Year are drawn from evidence gathered by our extensive language research program, including the Oxford Corpus, which gathers around 150 million words of current English from web-based publications each month. Sophisticated software allows our expert lexicographers to identify new and emerging words and examine the shifts in how more established words are being used.

Dictionary editors also flag notable words for consideration throughout the year and use other sources of data to identify contenders.

We regularly take into account the many suggestions sent to us via social media.

The final Word of the Year selection is made by the Oxford Languages team on the basis of all the information available to us.

How Merriam-Webster chooses the word of the year is more data-driven and relies only on the dictionary’s searches, which we might expect given the source:

A high-volume lookup most years, authentic saw a substantial increase in 2023, driven by stories and conversations about AI, celebrity culture, identity, and social media.

After digging for more information about the selection process, I found a 2018 video titled, “Behind the Scenes.” An editor-at-large provides a little more detail: “Merriam-Webster’s word of the year is determined by our online dictionary lookup data. The word must show both high volume of traffic and show year-over-year increase in lookups at Merriam-Webster.com.”

With its multiple, nebulous meanings, authentic, or authenticity, would inspire questions. The increase in searches particularly makes sense given one of the runners-up, deepfake. But the selection process could be more “worthy of acceptance,” one of the dictionary’s definitions of authentic.

Chevy Ad Makes People Cry

Emotional appeal as a persuasive tactic is fully evident in a new Chevrolet ad. Grandma has dementia, but a Chevy helps her remember.

In the video, a granddaughter takes grandma for a ride in her 1972 Chevy Suburban, tarped in the garage for who knows how long but running flawlessly. During the five-minute commercial, we hear John Denver playing on the car’s ill-fated 8-track tape.

Grandma awakens during the journey, remembering the old days and speaking in complete, cogent sentences. She returns to her family, seemingly fully recovered.

Chevrolet’s head of marketing said the ad was created “with help” from the Alzheimer’s Association:

We talked a lot about reminiscence therapy—not that it's a cure or a solve, but the power of music, the power of memories are things that can enable the person going through it to feel more comfortable. And the people that are the caregivers that are surrounding them, to also feel more comfortable.

A clinical chaplain tells me it’s not uncommon for people with dementia to get reoriented in familiar situations (like listening to “Sunshine on My Shoulders”), although the extremes in this case are unlikely. Chevy tries to avoid this problem by calling it a “good day,” but we might consider it a “miraculous day.” A Yahoo! article also points out, “It’s worth noting, though, that people with Alzheimer’s may not recall short-term memories, as the ad’s grandmother does when she realizes she’s due back for Christmas dinner.”

I wonder how folks at the Alzheimer’s Association feel about the ad. They might worry about false expectations for people with dementia. But I get it: It’s a fantasy. That’s what Christmas—or advertisements—are often about. I teared up when grandma and grandpa reunited too.

Maybe Chevy can change the title. The generic, “A Holiday to Remember,” appeases those who don’t celebrate Christmas. But the lights, red and green decorations, pinecone wreath, and that Lands’ End sweater all scream Christmas. Even grandma says at the end, “Merry Christmas.”

Musk Apologizes and Curses Advertisers

After losing major advertisers on X, Elon Musk illustrates communication lessons about apologies and rebuilding image. At least two parts of an interview with Andrew Ross Sorkin are worthy of class discussion.

Starting Around 8:15

The first relates to Musk’s agreement with an X post about a antisemitic conspiracy theory. Musk tried to backtrack by posting explanations, which he said were “ignored by the media. And essentially, I handed a loaded gun to those who hate me and to those who are antisemitic, and for that I am quite sorry.” Entwined in his apology is Musk as victim, which typically doesn’t play well in rebuilding image. Apologies focus on those affected—not the actor.

Another good lesson for business communication students is Musk’s regret. He said he “should not have replied to that particular person, and I should have written in greater length as to what I meant.” A leader should know that even liking a post, no less writing, “You have said the actual truth,” carries tremendous weight. Perhaps X, with its entire founding based on short posts, is not the best medium to discuss theories of race. [Side note: Musk clarified during the interview that “tweets” were more appropriate when Twitter allowed only 140 characters. He prefers “posts” now.]

Musk visited Israel, a trip he said was planned before the X post incident. Still, the visit looked like, as Sorkin said, “an apology tour.” Musk denied the accusation, repeating the phrase “apology tour,” despite what crisis communicators might advise. Musk posted, “Actions speak louder than words." Yes, they do, so the post itself is odd. People can draw their own conclusions about his visit to Israel. The Washington Post reported that few advertisers have been positively moved by his visit.

Starting Around 11:15

When Sorkin started speaking about advertisers, Musk interrupted to say, “I hope they stop [advertising].” Understandably, Sorkin looked confused, but Musk continued, “Don’t advertise. . . . If someone is going to try to blackmail me with advertising, blackmail me with money? Go f—- yourself.” Sorkin was speechless at this point, and Musk repeated the command and asked, “Is that clear? I hope that it is.” We hear titters in the audience, a mix of shock and embarrassment.

Where’s the line between confidence and arrogance? Students certainly will have opinions on that topic. In fairness, Musk gets quite philosophical later in the interview. He comes across as authentic and somewhat vulnerable, revealing his personal struggles as well as his commitment to the environment and his business plans. He also expressed disappointment about OpenAI, having named the platform, which he said “should be renamed super-closed source for maximum profit AI.” That got a genuine laugh.

Avoiding Shopping Scams and Other Online Deception

Talking about online retail scams is one way to remind students to evaluate websites critically. A Wall Street Journal quiz shows that younger people are susceptible to shopping fraud, despite what students might think about older people’s vulnerability.

The U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) describes signs of consumer fraud:

Fake websites and apps

Email links

Making payments on unsecure sites

Using public wifi to shop or access sensitive information

Package delivery confirmation scams

These traps seem obvious—until we fall for them. If students don’t admit being duped, maybe they’ll talk about someone who was or a fraudulent site or message they avoided.

If you cover Cialdini’s Seven Principles of Persuasion (including a new one—unity), students might identify how online retailers use each. They can find examples on their favorite shopping websites and discuss how ethically the principle is used. Students will easily find examples of scarcity (Cyber Monday! Giving Tuesday! Black Friday!).

He's Back: OpenAI Announces Sam Altman's Return

After more than 700 employees threatened to quit, Sam Altman and Greg Brockman agreed to return to OpenAI. The news was announced on X, where most of the communications have taken place—perhaps symbolic of the company’s losing control of the message. Nothing yet appears on the OpenAI blog, where Altman’s termination was first announced.

On the OpenAI X account, we see the smiling, reunited group and an announcement of the new board:

We have reached an agreement in principle for Sam Altman to return to OpenAI as CEO with a new initial board of Bret Taylor (Chair), Larry Summers, and Adam D'Angelo. We are collaborating to figure out the details. Thank you so much for your patience through this.

Formal announcements are missing from Microsoft’s blog too. Instead, posts by Altman and Nadella are chronicled with Nadella’s two previous posts about the situation. Two tired to press the shift key, Altman restated his commitment to the company and the team:

Sam Altman: i love openai, and everything i’ve done over the past few days has been in service of keeping this team and its mission together. when i decided to join msft on sun evening, it was clear that was the best path for me and the team. with the new board and w satya’s support, i’m looking forward to returning to openai, and building on our strong partnership with msft.

Satya Nadella: We are encouraged by the changes to the OpenAI board. We believe this is a first essential step on a path to more stable, well-informed, and effective governance. Sam, Greg, and I have talked and agreed they have a key role to play along with the OAI leadership team in ensuring OAI continues to thrive and build on its mission. We look forward to building on our strong partnership and delivering the value of this next generation of AI to our customers and partners.

Both messages say just enough, without blame or regret. Any explanation, for example, of a lost Microsoft venture, would only raise more questions. Clearly, they both want to move on, which is a theme: employees seem done with the drama, and even some of us watching have had enough.

Emmett Shear, who served as the second interim CEO for about a minute and a half, also expressed his gratitude on X:

I am deeply pleased by this result, after ~72 very intense hours of work. Coming into OpenAI, I wasn’t sure what the right path would be. This was the pathway that maximized safety alongside doing right by all stakeholders involved. I’m glad to have been a part of the solution.

For now, the drama is over. But OpenAI is a changed company, with new, self-imposed hurdles. Communication will need to be a top priority, and perhaps more of it will take place through more traditional channels. The new, experienced board members likely will have ideas for how to rebuild the company’s reputation, and they might, at some point, address whatever rifts caused Altman’s termination to start this chain of events.

Random: I’m laughing at the Microsoft Teams jokes. People reacted to Brockman’s first post that Altman was fired over Google Meet. Here are a couple of recent clever posts:

In response to Altman’s post about returning:

The lengths this man will go to not use Microsoft teams (@isroprisdead)

In response to Brockman’s post about returning:

blink twice if it’s bc of ms teams (@gajeshnaik)

Is Snoop Dogg Vulnerable or Self-Promoting?

Snoop Dogg’s November 16 announcement that he’s quitting “smoke” sounds as though he’s struggling with a marijuana addiction. But further inspection raises questions about his intentions.

Snoop Dogg has a few cannabis-related businesses. He owns the marijuana brand Leafs by Snoop and Uncle Snoop’s, which launched Snazzle Os, onion-flavored, infused crispy snacks. Other planned projects include virtual cannabis items “authenticated by non-fungible tokens [NFTs].” A partnership with Martha Stewart produced Best Buds Bags, fancy bags to hold the duo’s BIC EZ Reach lighters on the outside.

One day (November 15) before his giving-it-up announcement, Snoop was quoted about the bag:

“This bag’s got it all. From my favorite lighter, favorite color, and dime-sized secret stash pockets to stash my favorite herbs.”

On November 19, he announced that he’s partnering with a smokeless fire pit maker, Solo Stove:

I love a good fire outside, but the smoke was too much. Solo Stove fixed fire and took out the smoke. They changed the game, and now I’m excited to spread the love and stay warm with my friends and family,

Vulnerability is great unless it’s used for personal gain; then, it’s inauthentic and more like persuasion or manipulation. To be fair, he didn’t specify what kind of smoke he was quitting, but X replies indicate I’m not the only one who drew the cannabis conclusion. Maybe this was intended as a joke, but I didn’t find it funny.

New Baffling Comms About OpenAI Leadership Shuffles

Even the best communication can’t contain this much damage. The OpenAI saga, starting with the surprise firing of the CEO, illustrates the power of employee activism and the importance of communication planning.

The OpenAI board’s poor planning and decision making have led to angry investors, the loss of several key leaders and, as of now, more than 700 additional employees threatening to quit if the board doesn’t resign. The petition was fueled by employees posting on X, “OpenAI is nothing without its people.”

Employees have power because of their numbers and because of Microsoft’s promise to hire them, according to the signed letter. However, they also demand that Sam Altman and Greg Brockman be rehired, which may be unlikely since Microsoft quickly hired the pair to start a new subsidiary. In a 2:53 am, cover-all-bases tweet, Satya Nadella expressed continued confidence in the OpenAI team, and then slipped into the same paragraph Microsoft’s hiring of OpenAI’s two outsted leaders to start the new venture: “And [by the way] . . . .”

The employees who may join them include Mira Murati—the first to sign the letter—who was appointed interim CEO and replaced within two days. The biggest surprise might be #12 on the list—Ilya Sutskever, whom earlier reports blamed for the termination decision. Sutskever’s “regret” tweet doesn’t quite take responsibility, focusing on his “participation” (and if he were just following along) and his intention (which scarcely matters compared to the impact):

I deeply regret my participation in the board's actions. I never intended to harm OpenAI. I love everything we've built together and I will do everything I can to reunite the company.

Further confusing those of us on the sidelines—or perhaps simply displaying an impressive swell of forgiveness—Altman replied with three heart emojis.

One obvious lesson for business communication students is to think carefully before making major changes. Faculty teach communication planning that considers who needs to know what information and how each audience might react to the news. The board clearly underestimated negative reactions by investors and employees.

As this circus continues, I’m sure students will learn more about what to do and what not to do when communicating change—and making good business decisions.

Botched Comms About Altman's Departure from OpenAI

After backlash following the sudden termination of CEO Sam Altman, the OpenAI board is in a bind. Their minimal communications and what seems like an impulsive decision caused problems inside and outside the company. The latest news is that Altman may return because of investor pressure—and because he and a few employees who resigned in protest started, within hours, setting up a competitive company.

The Board’s initial statement cites “safety concerns tied to rapid expansion of commercial offerings.” Although his termination seems shocking, we don’t know the level of friction between Altman and the board. This article describes the possible ideological differences between Altman and the board, which are more subtle than what some describe as differences between “doomers” and “accelerationists,” with more focus on how to rather than whether to expand generative AI

The company statement doesn’t say much, yet is “unusually candid,” as a Wall Street Journal writer put it:

Mr. Altman’s departure follows a deliberative review process by the board, which concluded that he was not consistently candid in his communications with the board, hindering its ability to exercise its responsibilities. The board no longer has confidence in his ability to continue leading OpenAI.

“Candid” seems to be the word of the day. The WSJ writer means frank or forthcoming, while the board writer means truthful—both relate to integrity.

OpenAI President Greg Brockman was excluded from the meeting and resigned shortly after, writing on X that he was shocked too. Messages from Brockman and Altman to staff were short and professional. Other researchers resigned soon after. Altman has been posting his gratitude and potential plans regularly on X.

Microsoft tried to contain the damage. Without prior notice, CEO Satya Nadella posted a short statement expressing his continued confidence in the company. He referenced “Mira,” Interim CEO Mira Murati, and said nothing else about leadership changes. Still, Microsoft shares fell 1.7% by Friday’s close.

The OpenAI COO also tried to control damage in an email to staff that confirmed the decision was about a “breakdown in communications” (no kidding!) and not about “malfeasance.”

Students might be interested to learn more about the unusual governance structure of OpenAI. As a nonprofit board (in this case, only six members), they have more control over OpenAI’s leadership and operations than do investors of the subsidiary. Still, investors—and employees and the public—can and certainly are voicing their opinions. Whether or not Altman returns, the messaging will be interesting to watch.

Meta Lawsuit Demonstrates Claims and Evidence

A lawsuit filed against Meta by 33 states provides claims and evidence of manipulation, most significantly, a “scheme to exploit young users for profit.” Students might be interested in analyzing the suit and drawing their own conclusions.

Although a lawsuit typically isn’t considered business communication genre, this one demonstrates a few features faculty teach for writing reports. The first is a detailed table of contents with message titles, or “talking headings.” Students can read them and see whether they form a complete argument. They’ll notice major and minor claims and can analyze the evidence provided for each.

The “Summary of the Case” (Case Summary?) serves as a report executive summary. On pages 1 – 4 (6 – 9 in the PDF), the report outlines the major arguments. The organization is standard for legal briefs but weird to business communicators. We see a numbered list of paragraphs with no relation to each other. Paragraph 2 lists four parts of Meta’s “scheme.” Paragraphs 3 and 4 explain the first and second parts; paragraph 5 continues describing the second part, and so on. The concept of a subheading is lost.

Of course, legal writing is its own specialty. But students can draw comparisons to business reports as they dissect the arguments against the parent of the popular Instagram. The case also is interesting because the litigation approach is new—similar to those of suits against tobacco and pharmaceutical companies that claimed consumer harm.

FDIC's "Toxic Workplace" and an Activity

As Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) Chairman Martin Gruenberg faces pressure to resign, students can explore what a “toxic workplace” looks like. Without getting too detailed, they could describe their own experiences—when they have felt uncomfortable during jobs and internships.

In my persuasive communication and organizational behavior classes, I used a variation of an activity from Mary Gentile’s Giving Voice to Values that could be useful as you discuss the FDIC example. In the FDIC situation, speaking up didn’t make a difference. Still, reflecting on students’ own experience may inspire them to take action and have an impact in the future.

A Wall Street Journal investigation revealed multiple leadership problems dating back to at least 2008 at the FDIC. Complaints went unresolved and sometimes resulted in promotions of those accused. Although Black employees won a $15 million class action suit in 2000, discrimination complaints continued. Workers claim that sexual harassment and bullying is part of the culture.

FDIC leadership is taking no accountability and saying little in response to the published investigation. An official told the WSJ that the agency "has no higher priority than to ensure that all FDIC employees work in a safe environment where they feel valued and respected. Sexual harassment or discriminatory behavior is completely unacceptable. We take these allegations very seriously." Students will recognize this as meaningless boilerplate. Because the story is so visible and the reporting is so clear, the agency is better off demonstrating humility—recognizing failures and, if nothing specific at this point, at least describing plans for corrective action.

Taking Action

For this activity, you’ll compare two examples from your work or other experience.[1] The purpose of this exercise is to see how you have taken action in a situation that conflicted with your values. Then, you will analyze a time when you didn’t take action to see how you could have handled the situation differently.

Individual Planning Questions

First, think of a time when you were expected to do something that conflicted with your values, and you spoke up or acted in some way to address the situation.

Briefly describe the context.

What inspired you to do something?

What did you do and how did it impact others?

What are some things that would have made it easier for you to take action in this situation? Which of these were under your control, and which were outside your control?

In retrospect, how did you do? You don’t need to be too self-critical, but think about what would have been ideal in the situation.

Next, think of another situation in which you did not speak up or act when you were expected to do something that conflicted with your values or ethics.

Briefly describe the context.

What prevented you from speaking up? What would have motivated you to take action?

What are some things that would have made it easier for you to take action in this situation? Which of these were under your control, and which were outside your control?

In retrospect, what could you have done differently?

Partner Feedback

If you can work with a partner, discuss your responses and learn from each experience.

When talking about your own situation, you don’t need to defend your actions or be too critical. When you listen to your partner’s situation, you can ask clarifying questions or share similar experiences, but try not to judge the decision. Like you, your partner may be sensitive about actions taken or not taken.

At the end of your conversation, summarize the main learning points. What would you like to do more of in the future to develop leadership character?

[1] This activity is adapted from Mary Gentile, Giving Voice to Values (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 51–53.

Recall Notices About Metal in Chicken Nuggets

Recalls about “foreign matter” in food can be tricky to communicate. Tyson and USDA notices illustrate accountability and bad-news messaging for students to compare.

Audiences and communication objectives are similar for all recall notices. For the company and government agency, the primary audience is customers, and both organizations want customers to avoid using affected products. Messages clarify which products have been affected (typically product types, distributors, and locations), and companies offer a refund for returned products. Companies have an additional objective—to maintain brand image.

In this case of the “Fun Nuggets” recall, the USDA message is straightforward, starting with “Tyson” as the actor recalling the product. The notice describes the recall issue this way:

The problem was discovered after the firm notified FSIS that it had received consumer complaints reporting small metal pieces in the chicken patty product.

There has been one reported minor oral injury associated with consumption of this product.

With clunky language, the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) subtly promotes itself by describing what the agency does to follow up:

FSIS routinely conducts recall effectiveness checks to verify recalling firms notify their customers of the recall and that steps are taken to make certain that the product is no longer available to consumers.

The Tyson message also starts with the main point up front but emphasizes the “voluntary recall,” which is typical but a bit strange. Would the company need to be convinced to recall the product in such a case? Still, the writer chooses “out of an abundance of caution,” a near-cliché to describe the decision:

A limited number of consumers have reported they found small, pliable metal pieces in the product, and out of an abundance of caution, the company is recalling this product.

At least two more differences between the messages are notable. “Pliable” does sound better, and of course, Tyson doesn’t mention the “minor oral injury.” Tyson also states, “a limited number” of customer complaints, as any company would in a crisis situation to contain the damage. Stating a specific number also might convey an unpleasant image, which I have in my head, of an 8-year-old screaming at a kitchen table.

The FSIS message states where products were distributed, which seems useful, while the Tyson message includes a product photo, which seems essential. I’m guessing the FSIS wouldn’t send an agent out to buy a bag to take a picture, but they could lift the image from Tyson.

Emotions Drove a Football Manager's Comments

A football writer offers a lesson for all business communicators: “Maybe managers shouldn’t give interviews straight after games.” Similar to other business situations, emotions run high, and people need to take a beat before they speak or write. Student athletes and fans will be particularly interested in this story, but the example is for anyone who reacts before thinking through the consequences.

Arsenal Football Club (soccer to Americans) manager Mikel Arteta took an interview after a disappointing game. He disputed a goal call:

We have to talk about the result because you have to talk about how the hell this goal stands up and it’s incredible. I feel embarrassed, but I have to be the one now come here to try to defend the club and please ask for help, because it’s an absolute disgrace that this goal is allowed. . . .It’s an absolute disgrace. Again, I feel embarrassed having more than 20 years in this country, and this is nowhere near the level to describe this as the best league in the world. I am sorry.

Critics called Arteta’s reaction “disproportionate.” Such language as “how the hell” and “absolute disgrace” reflect a far greater injustice. I’ll leave the analysis to sports enthusiasts, but it seems like a questionable call—not an outrage.

The trouble worsens when the Arsenal Football Club defends Arteta in a statement, which included unequivocal support: “Arsenal Football Club wholeheartedly supports Mikel Arteta’s post-match comments.” The Athletic describes what business communication faculty would conclude, comparing the response to a crisis situation:

But for a football club to release an “official statement,” once upon a time the sort of thing reserved for managerial dismissals and so forth, about a marginal refereeing decision they disagree with, is extraordinary.

Over-reactions are difficult to withdraw. Arsenal supported the manager, which generally is a good corporate practice, but doubling-down on exaggeration makes management look defensive and lacking humility, as if they know a wrong was committed but are stuck.

Of course, a better approach for Arteta is to have waited a bit, as the writer suggests. It’s the same for business communicators. Write an email while angry but don’t send it until a day or so later. During a difficult interaction, pause and step away if you need to. Most often, an immediate response, as this situation shows, isn’t needed.

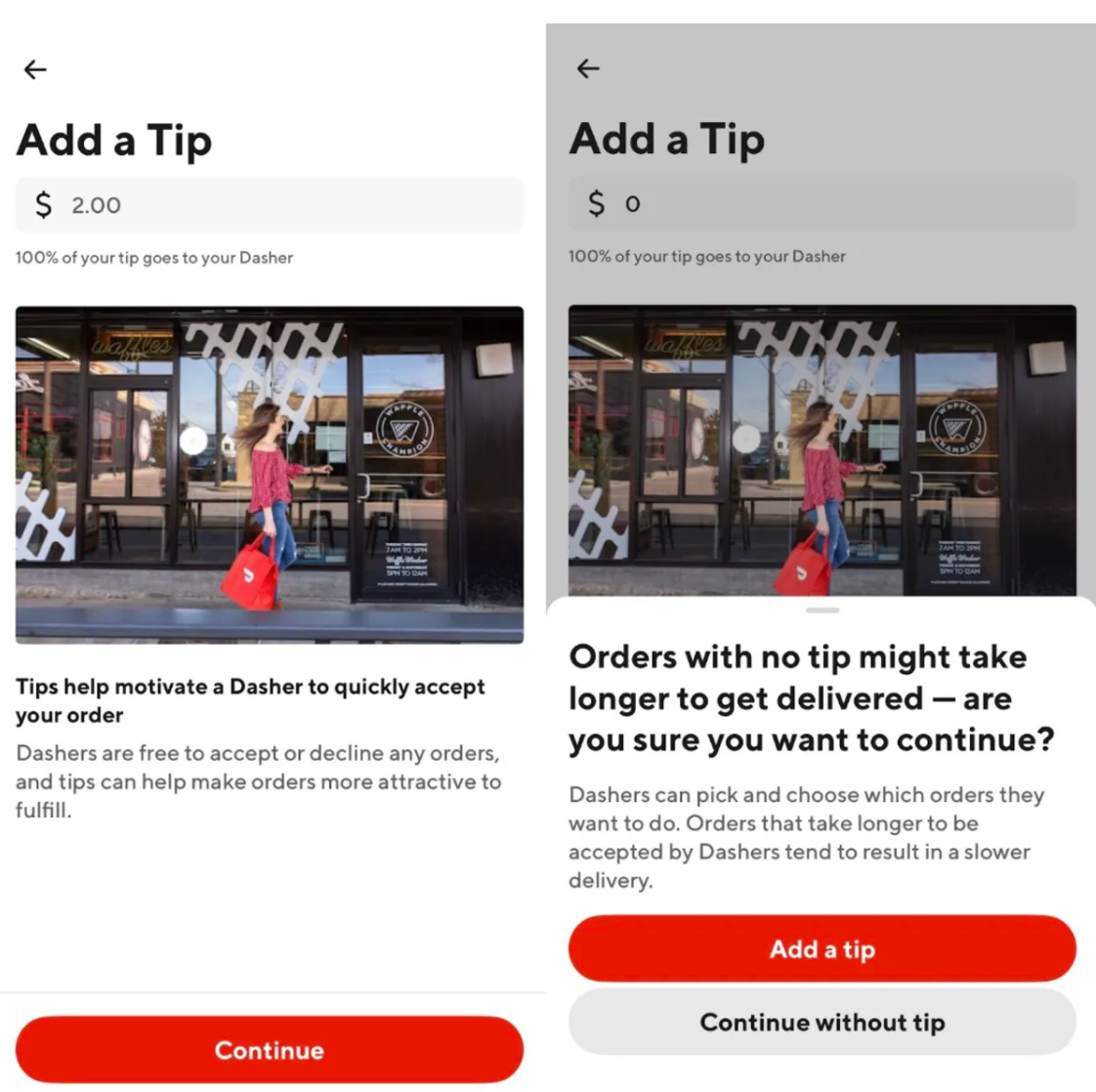

DoorDash Delays Orders Without Tips

DoorDash is piloting a new screen warning customers that no tip could mean a delayed order. The messaging illustrates principles of persuasive communication.

DoorDash’s message framing encourages tips, even though the process is punishing. In the statement title and subtitle, the company emphasizes “quality” and “the best possible experience for Dashers, consumers, and merchants.” These frames are clever alternatives to claims about pay fairness because that would reflect poorly on the company, which some customers call out in tweets about paying a living wage.

Another strategy DoorDash uses is deflecting responsibility, or blame, onto the drivers:

In the event that a consumer chooses to not leave a tip, we also let them know that their order may take longer to be accepted as a result. This is because—as independent contractors—Dashers have full freedom to accept or reject offers based on what they view as valuable and rewarding. Since launching this test, we’ve seen a meaningful decrease in no-tip orders.

In that last bit, DoorDash evokes peer influence, which also is used at the beginning of the statement: “That’s why we encourage consumers to show their appreciation by tipping—and the vast majority do.” The idea is for customers to get on board with the majority: if they hadn’t been tipping, as most do, then they should begin now, as more have.

The statement rambles a bit, and students might identify a contradiction towards the end:

The test does not impact DoorDash’s commitment to quality or how orders are fulfilled. Our goal is to deliver the best possible experience—regardless of the amount a consumer tips—on each and every order.

But isn’t the objective of the pilot—more tipping—to improve quality? For most people, a delayed order isn’t the best possible experience.

Customers point out another contradiction, which is tipping before service. But, as Michael Lynn, who has studied tipping for decades, says, “Ultimately, social approval’s the main reason we tip,” so DoorDash’s peer influence strategy should work. For more about the morality of tipping, David Brooks offers one perspective, which is that we should tip generously regardless of service.

"Open to Work" and Other Desperations

Although LinkedIn offers an “open to work” option, at least one recruiter says it’s the “biggest red flag" for employers. This reminds me of other ways students inadvertently appear desperate to recruiters.

LinkedIn explains the feature, which offers the option to show the banner to all LinkedIn members or only to recruiters. Users might select all members, thinking about networking strategies, but this might increase the look of desperation. LinkedIn also explains, “[W]e can’t guarantee complete privacy” because, if someone is still employed, recruiters at the company might find out from other recruiters that they’re on the market.

One recruiter compares job seeking to dating and encourages “exclusivity.” Business communication faculty may refer to Cialdini’s scarcity principle: people want what they can’t have.

We coach students to be more selective in their search. When a recruiter or hiring manager asks, “What’s your ideal job?,” students should have one in mind—not too narrow, but not too broad either. “I’ll do anything. I just want to work for xx” likely won’t inspire an offer. This reminds me of reading applications for the Cornell Nolan School of Hotel Administration. Many students would write that they applied because “it’s the best” program. That answer says little about the applicant’s decision process—or maybe the answer says it all.

On the other hand, students who lie about multiple job offers are playing a dangerous game. In addition to the obvious issues of integrity, college recruiters talk.

Networking requires more effort than a banner. Years of curating a network, which develops from supporting and being helpful to others, results in people who care about an applicant and want to see that person succeed. For students, this is more challenging but starts during school.

John Oliver Blasts McKinsey

Last Week Tonight produced a 26-minute segment criticizing management consultancy McKinsey. Students can decide whether John Oliver was fair in his conclusion that, “McKinsey’s advice can be expensive but obvious, its predictions can be deeply flawed, and it’s arguably supercharged inequality in this country.” He contrasts these conclusions with the CEO saying, “Our purpose is to create positive, enduring change in the world.”

Here are a few areas to explore, or you can just show the fake recruiting ad starting at 23:00, which is pretty funny.

Timing

I’m curious why Oliver created this segment now. McKinsey’s role in the opioid crisis, which he covers at around 12:00, was most highly litigated back in 2021 - 2022. He doesn’t point to anything specific since then.

Evidence

To make his points, Oliver uses a variety of evidence but mostly examples in the form of stories. If this were a serious rebuke of McKinsey, students might expect more data. I also question the many references to a 1999 film. Maybe things have changed since then? The inexplicable timing contributes to the segment feeling like the attack that it is, rather than a balanced piece. But I forget: This is “late-night news,” not actual news.

The Example of Eliminating Signatures

The example of identifying cost savings for an energy client is just silly (at 7:30). I wonder whether this is just a terrible example—or whether more information about the situation, or more examples in the original video, would make it less embarrassing. We don’t see the context.

Oliver’s Indignance

Oliver jokes about his British accent sounding “smug” (6:33), but his style is part of the reason I don’t watch him or other talk-show hosts. I’m guessing a lot of students find him funny because of his style. This might start an interesting discussion about delivery styles.

McKinsey’s Response

I don’t see any response from McKinsey, and I don’t think it would be wise. But it’s a worthy discussion point with students. Why wouldn’t the company respond? What are the arguments for responding? What, if anything, could the company say or do?

Other Perspectives

Business communication faculty—and journalism faculty—teach students to offer multiple, sometimes conflicting perspectives. At around 21:00, Oliver does present other sides. He acknowledges that other consulting firms sometimes act unethically or have questionable client relationships, which (sort-of) addresses criticism that he’s singling out McKinsey. Oliver also describes how McKinsey responded to an inquiry from the show a few days before airing and admits that he’s presenting examples, which McKinsey would say don’t represent their work. But he argues against these claims by saying that the harm McKinsey has done outweighs the good.

Character

Starting at around 22:30, Oliver calls out the character dimensions students will associate with this story. He calls for greater accountability and transparency, which I describe as part of integrity. That cues up the parody McKinsey recruiting video, which starts at 23:00 for students’ enjoyment.

Of course, the entire segment raises questions about Oliver’s own integrity. Then, again, the show is what it is intended to be: entertaining.